Today AMD is introducing its 7th generation of mobile APUs codenamed Bristol Ridge and Stoney Ridge. These products were previously announced back in April and have been on AMD’s public road map since 2015. Bristol Ridge is a refined version of last year’s Carrizo APU. This is a very similar situation to what we saw with AMD’s Richland APU which was a refined version of Trinity. It seems that AMD has created its own version of Intel’s tick-tock strategy by creating an initially aggressive product one year and then refining it without major changes in the next.

Perhaps the most interesting piece of this launch is Stoney Ridge. As the follow on to last year’s Carrizo-L, Stoney Ridge has its work cut out for it. Intel’s Atom lineup has become extremely competitive in the last two years. Even with the ongoing personnel cuts and reorganizations ours sources tell us that there are at least two more generations of Atom processors in the pipeline at Intel. This means that in order for AMD to compete it needs to take this segment of the market more seriously. Carrizo-L wasn’t good enough. It’s still an open question if Stoney Ridge can retake the once dominant position that AMD held with Brazos and Kabini in this high volume market.

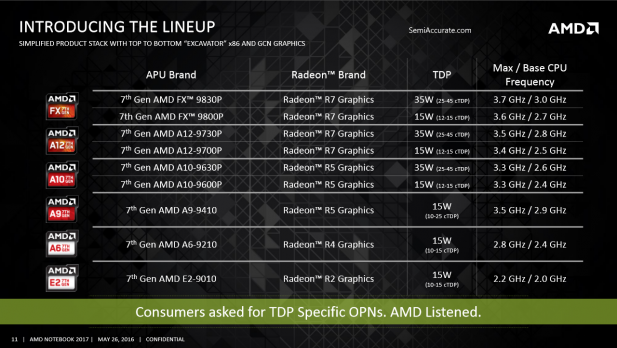

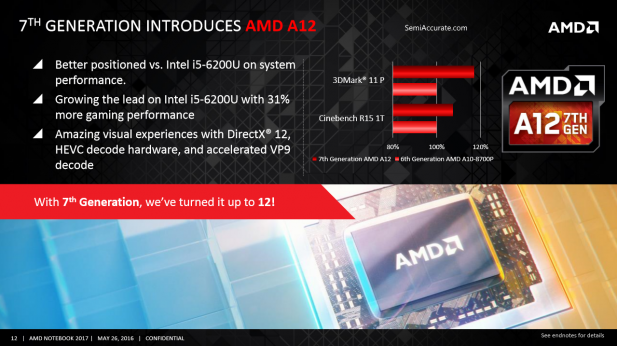

I remember a time when the A8 was the top of AMD’s APU stack. Then for the longest time it was A10. At this rate by 2020 we’ll be talking about AMD’s A16 APUs. In any case AMD’s new second best chip is dubbed the A12. Since last year AMD has begun using its FX branding on its highest performance mobile APUs. That trend continues this year with an FX branded SKU on top, followed by A12 and A10 SKUs.

In a forward thinking move AMD has defined separate model numbers for each of its Bristol Ridge parts based on the TDP selected for that design by the OEM. Chips capped at a 15 Watt TDP will Axx-9x00P model number while chips with a 35 Watt TDP will have a Axx-9x30P model number. Thus there will be some indication of the laptop’s TDP cap in the processor’s model number. Chips sold to OEMs as 35 Watt parts can be configured to use a TDP anywhere in the 25 to 45 Watt range. 15 Watt parts will be configurable between 12 and 15 Watts.

More importantly Bristol Ridge’s clocks are really high compared to AMD’s older designs. Typically AMD’s mobile APUs have had based clocks around 2 Ghz and with turboing up into the 3 Ghz range. With Bristol Ridge we have base clocks around 3 Ghz and turboing up into the high 3 Ghz range. This is a rather impressive improvement.

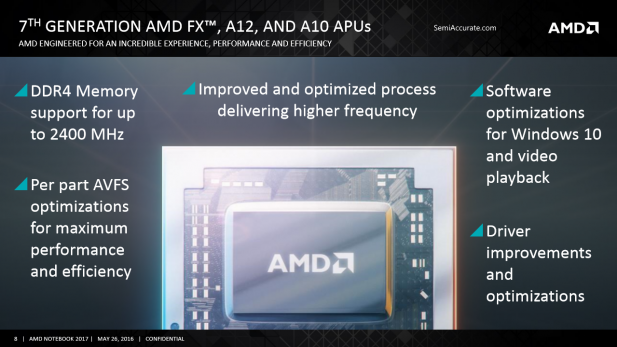

For its part AMD says that it’s done quite a bit of work to polish Carrizo in the Bristol Ridge chips we’re seeing today. While it’s still built on one of Global Foundries bulk 28nm process nodes AMD says that Bristol Ridge uses a newer revision of that technology that incorporates some process technology optimizations that were not present in Carrizo.

Additionally AMD’s had the better part of a year to profile and fine tune Carrizo’s power management hardware and firmware. The effect of which has been to implement a more aggressive version of the Adaptive Voltage-Frequency Scaling (AVFS) technology it first introduced with Carrizo. AVFS is a very potent technology in that it utilizes real-time sampling hardware to sample at ten points spread around the CPU core for changes in power, voltage, temperature, and frequency.

AMD has also done some software tuning for Bristol Ridge by working with Microsoft to optimize the Windows power management scheme to reduce power consumption during video playback.

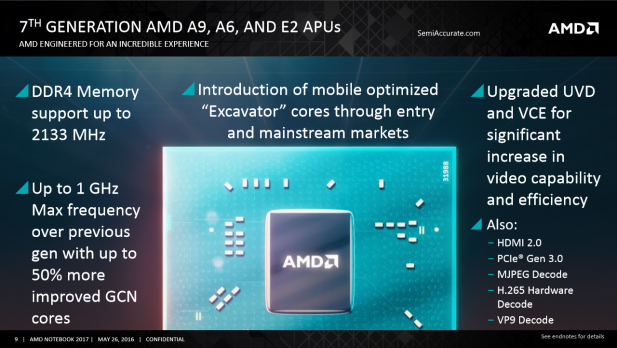

The most important improvement that Bristol Ridge offers is DDR4-2400 support. Carrizo was limited to DDR3-2133, which while good, wasn’t good enough to keep its GPU from running headlong into a memory bandwidth bottleneck. DDR4 both consumes less power than DDR3 and can reach higher clockspeeds. Of course DDR4-2400 isn’t mind blowingly fast but its a good bump and it beats out Intel’s DDR4-2133 specification for Skylake.

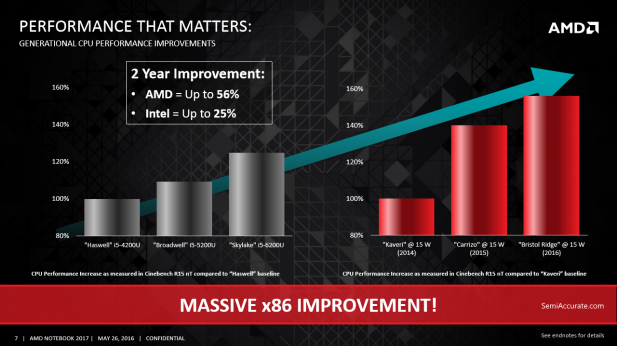

The argument that AMD’s making with this slide is that the performance of their mainstream mobile processors is increasing rapidly. This is true. But it’s also a bit misleading. Based on AMD’s footnotes for this presentation the bar for Bristol Ridge @ 15 Watts shown on this slide, with the tallest red bar, performs in absolute terms equivalently to the Haswell i5-4200U from 2 years ago, shown as the smallest grey bar, in Cinebench R15. To be clear matching Haswell @ 15 Watts is an impressive achievement. It’s just not quite the impression that this slide gives you.

AMD is trying to show us that it cares about premium design wins. This is one of the big issues that Anandtech pointed out in their Carrizo article at the end of last year. OEMs won’t put AMD’s chips into decently designed laptops. HP’s ENVY x360 is a good start. But HP has historically been the most pro AMD OEM in the market. The OEMs that AMD needs to work with to build premium laptops are Lenovo, Dell, and ASUS in that order.

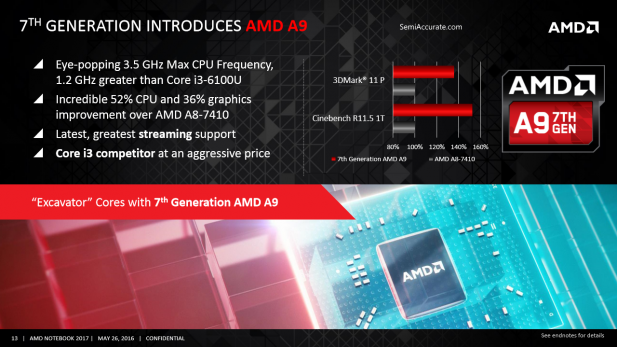

The low-end of AMD’s mobile product stack is composed entirely of Stoney Ridge SKUs. The A9, A6, and E2 monikers all belong to Stoney Ridge products now. When asked if small cores were dead at AMD the company’s representatives would not comment. But the appearance of AMD’s biggest core in its cheapest chips makes the path forward rather clear. One big advantage of bringing Excavator down to these price brackets is that cheap AMD-based laptops will see a massive year over year improvement in single threaded performance.

We inquired further with AMD about die sizes and transistor counts of its new mobile chips and they came back to us with some interesting figures. Bristol Ridge has a 250.4mm2 die with 3.1 billion transistors and Stoney Ridge has a 124.5mm2 die with 1.2 billion transistors. Both chips are built on Global Foundries’ 28nm bulk CMOS process.

The concept that Stoney Ridge is a half of Bristol Ridge seems to be further supported by these die size figures. Interestingly while AMD’s mainstream APUs have held constant at die sizes of around ~250mm2 for the last half decade the die sizes of their low-end APUs have consistently increased generation over generation. AMD’s first entry-level APU Zacate was 75mm2 chip paired with a 25mm2 southbridge. AMD’s second generation of this line Kabini had a 107mm2 die as did the third generation product Beema and the fourth Carrizo-L. At a slightly larger 125mm2 Stoney Ridge has 16% more die area to work with than Carrizo-L.

Stoney Ridge only offers support for up to DDR4-2133 memory rather than DDR4-2400 like Bristol. This is odd since it would appear that these two chips have the same basic memory controller and architecture. Never the less the biggest upgrades that Stoney Ridge brings to AMD’s low-end are the upgraded UVD and VCE engines coupled with the platform level enhancements like PCI-E 3.0 and aggressive power management features that were skipped in Beema and Carrizo-L.

While Carrizo-L only had 2 GCN CUs, Stoney Ridge bumps things up a notch with 3 GCN CUs. Stoney Ridge, like Bristol Ridge and Carrizo-L, is an SoC. SoC in AMD’s terms means that it has an on-die southbridge. Neither Bristol nor Stoney Ridge use the Polaris revision of AMD’s graphics cores rather they use the prior version referred to by AMD as 3rd generation GCN cores. Both parts are fully HSA 1.1 compliant.

It’s worth noting that this is not the first time we’ve come across Stoney Ridge. When AMD updated their embedded line-up earlier this year there were suggestions that Brown and Prairie Falcon, AMD’s embedded G-Series J and I Families of SoCs, were based on Stoney Ridge. AMD was evasive about the issue at the time. But based on the configurations that those embedded chips are offered in it now seems clear that Stoney Ridge came first to the embedded market. There are still some items that don’t quite add up though like the I family offering 4 GCN CUs and dual channel memory where as the Stoney Ridge we’re seeing here today has 3 GCN CUs and single channel memory. But I expect those distinctions will be made clear at eventually.

What we have today is the end to a bifurcated APU lineup from AMD. The debate between small core and big cores is now over; big cores won. The same basic IP now scales from ~250mm2 down to ~125mm2. From 45 Watts to 10 Watts. And hopefully now from $200 to $20 in a profitable manner. The impact of AMD’s new mobile products probably won’t be felt financially until we can see AMD’s Q4 2016 results. We’ll know at that point if Bristol and Stoney were the right choice.S|A

Thomas Ryan

Latest posts by Thomas Ryan (see all)

- Intel’s Core i7-8700K: A Review - Oct 5, 2017

- Raijintek’s Thetis Window: A Case Review - Sep 28, 2017

- Intel’s Core i9-7980XE: A Review - Sep 25, 2017

- AMD’s Ryzen Pro and Ryzen Threadripper 1900X Come to Market - Aug 31, 2017

- Intel’s Core i9-7900X: A Review - Aug 24, 2017